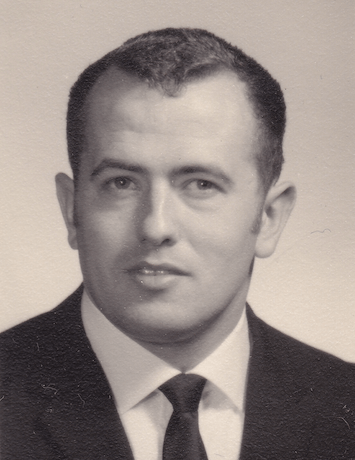

D. E. Larsen, DVM

I looked hard at the man seated behind the desk.

His dark hair was fading into a grizzled gray. His oversized nose had a mass of red pimples. I suspect it was Rosacea. The wrinkles in his face were smoothed a bit by its puffiness. His large ears actually added balance to his whole appearance. On somebody else, they would be considered large.

“What did you ask me?” I asked, not believing the question. This was my first experience with a financial aid office. I was getting ready to start my junior year in vet school, and my funds were exhausted.

Before I went into the Army, I could work a summer in the cheese factory and pay for a year of school. So I had no need for any aid in those years. Following the Army, I had four years of the GI Bill. With those payments of around two hundred dollars a month plus some part-time work, I finished twenty-four months at Oregon State without any debt.

The same was true for my first two years in veterinary school. But now, entering my clinic years in vet school, I would not be able to work part-time, and the GI Bill was exhausted. I was forced to seek financial aid.

“How much money do your parents make?” the man repeated his question.

I could feel a growing contempt for this man with a rumpled shirt and a belly hanging over his belt. I had worked with generals who were this man’s age and who would have little regard for this man.

“Would you look at me,” I said. “I’m not one of your twenty-year-old students who still takes his laundry home on weekends. I am twenty-eight years old, and I have a wife and three kids at home. I have six years of college under my belt, and I spent four years in the Army. I have not lived at home for ten years. I have no damn idea how much money my parents make, and I will be damned if I am going to ask them.”

“Well, Mister Larsen, I generally don’t talk with students who have six years of school, under their belts, and who don’t have some school debt. Unless their parents have paid for their schooling,” the man said.

This guy looked like he had been in the public trough his entire life. He probably has little understanding of how someone actually works for things he accumulates in life. I stiffed my stance in my chair.

“Are you suggesting that I am being less than honest with you?” I asked, and I continued without giving him a chance to answer. “I have virtually worked my entire life. After age ten or twelve, I haven’t spent a dime that I didn’t earn personally. I resent your insinuation.”

“I’m sorry that you took it that way,” the man said. “I was just explaining my observation from this desk. I have had a few of you veterans through here, and you guys, as a group, have a level of maturity that I admire.”

He’s trying to soften me up, now, I thought.

“My service was pretty plush compared to some guys in combat in Vietnam,” I said. “And a bunch of those guys never came home.”

“Yes, I know,” the man said. “Look, you and I have sort of got off on the wrong foot here. You, obviously, are qualified for financial aid. I will give you a packet of forms to fill out. You get those turned in, and we will send things to your bank for a guaranteed loan. Because you haven’t borrowed anything before this time, you are not eligible for grants or scholarships. I will put special processing on your folder, and your bank will have your information in a couple of days after you turn in those forms.”

“Thanks for the special consideration,” I said as I stood up and picked up the packet from his desk. “My wife will appreciate it, but she was hoping I would get a Pell Grant or something.”

“Yes, those grants are nice,” the man said. “But one of the requirements is prior school debt or a family with great need. You don’t qualify with six years of college paid for. Next year, we will be able to come up with a better package.”

“Thanks again,” I said as I shook the man’s hand. “We will have these papers filled out tonight and turned in tomorrow.”

I felt a little better about things as I left the office. At least the guy recognized the error of his ways. Maybe another veteran or two will benefit from my conversation with the man. But Sandy was not going to be happy about not getting a grant.

“What do you mean, we don’t qualify?” Sandy asked. “Why don’t we qualify for a grant?”

“The guy said if I had paid for six years of school without borrowing any money, I wasn’t poor enough for a grant,” I explained.

“Well, I don’t think that is fair,” Sandy said. “If fifty dollars a month from the Oregon GI Bill doesn’t qualify a family of five as poor, I don’t know what does.”

“We only have a couple of years left, and then I can go to work,” I said. “Living on borrowed money won’t be too bad for that amount of time.”

***

The man at the financial aid office was true to his word. I turned in the packet of papers in the morning, and the gal from his office called in the afternoon to say things were approved and sent to the bank.

The loan process was simple, the bank in Oregon sent me some forms to sign, and we were flush with money for the year.

The following year was better with a large Pell Grant. I think I graduated with a debt of around six thousand dollars. Chicken scratch compared to the debt students incur today.