D. E. Larsen, DVM

I was just finishing up in the surgery room after doing a spay on a small dog when Sandy appeared at the surgery room door.

“Larry is on the phone,” Sandy said. “He thinks he has a cow with a broken front leg. He wants you to get a look at her. If you are done here, you probably have the time to run out there now. At least enough time to get a look at her.”

“Okay, tell him I will run out and see if I can do anything with it,” I said. “It depends on where the fracture is located and how much he wants to spend on the cow.”

“After you pinned that calf’s leg for him, he will expect you to fix this one,” Ruth said.

“Yes, and he said that this was his favorite heifer, and she was due to calve in a couple of months,” Sandy said.

We hurried to finish the surgery and ensured the pup was fully recovered from anesthesia before jumping in the truck to run out to Larry’s place on the edge of town.

Larry had the heifer in his small corral. From a distance, it was obvious that the left front leg was fractured. It looked like a fracture just below the carpus.

“Larry, how did she do this?” I asked as I got out of the truck.

“I have no idea, Doc,” Larry said. “The wife noticed her out the kitchen window. She just limped up to the barn like she knew where to get help.”

“Let me get a rope on her. I don’t want to put her in the chute with that leg flapping around,” I said.

“Doc, I just can’t shoot this little gal. She is one of the few cows of mine with a name. I call her Alice, after a girl who used to work for us at the Busy Bee.” Larry said. “And even if I did, I couldn’t eat her. Can you fix a broken leg on a cow?”

“It’s just like everything, Larry, any more it’s just a money game,” I said. “We can send her over to Corvallis, and they will fix her for a few thousand dollars.”

“Well, I really like Alice, but let’s be reasonable,” Larry said. “If it will be that much, I will just have you do the shooting.”

“Let me look at her, and we will talk about what I can do,” I said. “Some fractures will heal if you just pen a cow up in a small pen where they can’t move around much. Especially fractures higher up in the leg where the bone is supported with a lot of muscle. This is lower on the leg, but maybe we can fashion a splint that will work.”

When I crawled over the fence into the corral, Alice didn’t move. I scratched her on the head, and she licked at my arm. She was content to just stand there while I looked at her.

I stepped to her side and rubbed her back before kneeling down beside her fractured leg. I ran my hands down her leg. The fracture was a clean break of her cannon bone, about one-third of the length below the carpus. This would heal well if we could get her in a splint.

When I stood up, Larry was holding the corral gate open for me.

“They make gates, Doc, for people who don’t like to crawl over fences,” Larry said.

“Larry, we can fix this leg with a Thomas splint,” I said. “We just have to get someone to make one for us.”

“Show me what you’re talking about, Doc,” Larry said.

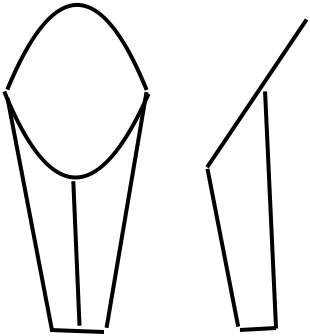

We walked over to the truck and drew a rough sketch of what I wanted.

“So, this needs to be made out of good solid steel, like half inch rod. The leg fits through the upper circle, and I will wire the hoof to the plate on the bottom. This has to fit snuggly in her armpit. You need to measure the distance from her armpit on her good leg to the ground and use that measure for the distance from the bottom edge of the circle to the footplate. The circle can be round, looking at Alice, I would guess twenty-four inches in diameter, and a round plate on the bottom with some holes drilled in it so I can wire the hoof in place.”

“I see. This is sort of like a crutch,” Larry said. “But won’t it wear of sore in her armpit?”

“I will pad it with cotton,” I said. “And we will need to pen her up in the barn for the duration of the healing, about six weeks.”

“They can make this down at the welding shop in no time,” Larry said.

“Good. You get it done, and I will be back at the end of the day and put it on,” I said. “Just leave Alice right where she is until then.”

When I returned in the late afternoon, Alice had hardly moved. I looked at the Thomas splint that Larry had made. It was heavier than I expected, but that was probably good, we didn’t want Alice to be too mobile while this fracture was healing, and she sure wasn’t going to bend this thing.

I used a cotton roll to pad the upper ring and secured it with heavy adhesive tape. Holding it beside her leg, it looked like it would be a perfect fit.

I put a halter on Alice and tied her to the corral fence.

“I think I can get this on with her standing,” I said. “If I can’t, we might have to lay her down. I will need an electric cord, Larry. I am going to drill a couple of holes in the edges of hooves so I can wire them to the base plate.”

Larry strung out an extension cord, and I drilled four holes on the outer edge of each claw. Then I carefully threaded the splint onto Alice’s leg. You could almost hear her relax when it was in place and providing her some support.

I took a roll of 20 gauge stainless steel wire, wired the hoof to the base plate, and finished by taping around the two sidebars to provide some internal support for the lower leg.

When I removed Alice’s halter, she immediately took a few steps, looking for some grass at the edge of the corral.

“That looks like it is going work like a charm,” Larry said.

“It will be like a part of her by the time we take it off,” I said. “But I want her penned for the next six weeks. I will swing by every week to make sure this is holding up okay. But I bet we could use this on an elephant, as sturdy as it is.”

“I told them what it was for and that you didn’t want the cow to be able to bend it,” Larry said. “They do a pretty good job down there. And they liked your sketch.”

***

I stopped by and checked on Alice every week. She was doing so well with the splint that I was tempted to take it off after 5 weeks but restrained myself.

When I arrived on my six-week check, Larry had Alice outside in the corral.

“I’m a little anxious to see how she does when you take this off,” Larry said.

“So am I, Larry, so am I,” I said.

First, I removed all the tape from the splint and palpated the fracture site. There was a lot of boney callous at the fracture site, and the leg was well healed. Some wires had broken on the hoof, but I snipped the others and pulled the foot free. Then I took the splint off.

There was only a minor abrasion in the armpit, nothing that required any attention.

Alice stood, holding her foot up momentarily, then took several steps. Then she walked around the corral, looking out at the other cows in the pasture.

“She has a limp, but that is expected for a time,” I said. “But I think we are home free. Her leg is solid. You should leave her penned tonight so she makes an adjustment to not having that splint to haul around and turn her out in the morning.

I could still see a slight limp when I drove by and watched Alice in the pasture the following week. I doubt anyone would notice it if they didn’t know her history.

Larry came in a couple of weeks later to pay the bill. He was happy.

“Alice had a calf a couple of days ago,” Larry said. “I can’t believe I almost shot her before I called you. I just couldn’t bring myself to shoot her. That was the best thing that ever happened.”

Alice was around for many years and popped a new calf every year. Larry made an excellent investment in repairing her leg.

Photo by Rabia Hanım on Pexels.

Larry’s previous story about a fracture –

https://docsmemoirs.com/2023/02/22/my-calf-needs-a-little-repair-from-the-archives/