D. E. Larsen, DVM

The girls were all waiting for me when I came through the door after work.

“We have kittens!” they all screamed in unison.

“We have lots of kittens,” Amy said.

“Both Sam and Mittens had kittens,” Brenda said. “Sam only had one kitten, but Mittens had seven.”

“Come on, we will show you,” Amy said as she tugged my arm.

So off to the garage we went. Dee tagged along with the two older girls in the lead.

Mittens was in her box, carefully tending to her large litter, and Sam was nearby with her single kitten.

I grabbed Sam and palpated her abdomen to ensure there weren’t more kittens that didn’t make it out. No kittens in her belly.

“And look at Mitten’s white kitten,” Brenda said.

Sure enough, in the tangle of kittens was a white kitten.

“I think that is a siamese cross kitten,” I said as I picked it up and checked its sex. “He is a boy. We will keep this kitten; he will darken like a siamese as he gets a little older.”

“Mom said we are not to pick the kittens up,” Brenda said as I returned the kitten to the box.

“I get to do things sometimes that Mom says not to do,” I said.

We left the mothers with their kittens and returned to the house to prepare dinner. Sandy was just finishing up getting Derek fed and in his crib. I started putting together the dinner.

The girls were all atwitter about the kittens all through dinner.

“Can we check the kittens after dinner?” Brenda asked.

“You can check them, but they need some privacy for a few days,” I said. “If you bother them too much, the mothers will move them. Maybe move them outside or hide them somewhere in the house.”

There was no slowing them down. The girls were done eating almost by the time Sandy got to sit down.

“Can we go check them now?” Brenda asked.

“You have to wait until Dee is ready to get down from the table,” I said. “And she will need some help washing up after dinner.”

That would have been a chore from hell any other day, but Brenda rushed Dee to the kitchen sink to wash up her hands and face after she climbed down from the table. Then all three girls disappeared into the garage.

Amy was the first to return, almost out of breath from the excitement.

“Sam stole the white kitten,” Amy said as Brenda and Dee rushed up behind her.

I got up and followed the girls to the garage. Sure enough, Sam had the white kitten snuggled up with her other kitten, and Mittens didn’t seem too bothered.

I picked up the white kitten and carefully returned him to his mother’s box.

“Why did she do that?” Brenda asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Maybe Sam thought she could help Mittens out with her bunch. Now let’s all go back in the house and leave the kittens alone for the evening.”

I checked the kittens one last time before going to bed. Sure enough, Sam had the white kitten in her box. I was tempted to leave it, but I carefully returned it to Mittens.

“Sam really wants that white kitten,” I said to Sandy as we got into bed.

“Both Sam and Mittens are black. Maybe she just likes the contrast,” Sandy said.

“If it keeps up, I am just going to let her have it,” I said.

Sure enough, Sam had the white kitten when the girls checked the kittens in the morning.

“I think Sam is just helping Mittens out,” I said. “I think we will let her adopt this little white kitten,”

“Brenda wants to call him Morris,” Amy said.

So Morris was raised by Sam. Sam was happy, Morris had little competition for milk, and Mittens was not bothered by the loss.

***

When Morris and his litter mates were still nursing, we made our move from Enumclaw to Sweet Home. Because we were going to be in an apartment initially, our eleven cats were delivered to my folks in Myrtle Point until we were in a house.

At Myrtle Point, cats were not allowed in the house. So our cats became barn cats.

“Why won’t Grandma let the kittens live in the house?” Amy asked.

“Grandma was raised on a farm, and cats and kittens were always in the barn,” I said. “The kittens will be fine. The biggest risk will be if the older cats leave to try to find their way back to Enumclaw.”

“You mean they would run away from Grandma’s?” Brenda asked.

“It probably won’t happen, but it is possible,” I said. “We have no other choice. They will just have to make do with the barn.”

***

When we finally were settled in our house on Ames Creek, we made the trip to Myrtle Point to gather all the cats. By some miracle, they were all there. And they had no adjustment with the move back to Sweet Home.

“I think Morris likes to live outside,” Brenda said shortly after we had the cats back home.

“He grew up in the barn at Myrtle Point,” I said. “He probably likes the freedom.”

It was not long after that discussion, and Morris was gone. The girls were crushed. The days turned into weeks, and the weeks turned into months.

Then one Saturday morning, we loaded everyone into the car to go to the lake for lunch. We were less than a quarter mile from the house when Amy screamed.

“There is Morris,” Amy said, pointing out the window. Morris was sitting in the middle of a cat road that led up to some timber.

I stopped the car and walked up the cat road for twenty yards.

“Kitty, kitty,” I called to Morris.

Morris turned and ran into the brush.

“Was that him?” Brenda asked as soon as I got back in the car.

“I am pretty sure that was him, but he wasn’t interested in being caught,” I said.

***

After that sighting, we would see Morris on multiple occasions. He was apparently living in the timber not far from the house. He evidently had no interest in coming home.

That was until one Sunday morning. Amy heard a cat meowing at the front door. She opened the door, and it was Morris.

“Let me pick him up,” I said. “He might not be ready for any hugs yet.”

I petted Morris, and he purred but made no effort to move. I picked him up, and there was the reason that he came home. His right hind leg was broken, a mid-shaft fracture of his tibia. I took him into the house and closed the door.

“Morris has a broken leg,” I said. “At least he knew where to come for help.”

Morris made a trip to the clinic with me that Sunday afternoon, and I called Dixie to come in and give me a hand with the surgery. He was like the plumber’s pipes. If I didn’t repair his leg today, it might be several days before I had the time.

Fractured tibias were probably the easiest of the bones to repair. I used a combination anesthesia of xylazine and ketamine. Then I made a small incision at the fracture site and placed an inter-medullary pin into the bone in a retrograde manner. The entire procedure took less than a half hour.

“Are you going to get an x-ray?” Dixie asked as I placed Morris back in the kennel for his recovery.

“I feel good about how things went together,” I said. “And I don’t think there is any need to document my work. I doubt if the girls will sue me for malpractice.”

“I wouldn’t be too sure about that,” Dixie said. “Those girls are all pretty fond of their cats.”

***

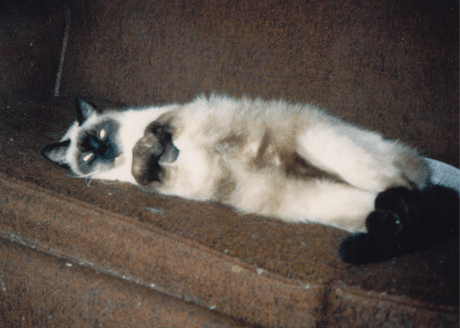

Morris healed well, and I removed the pin in six weeks, right on schedule. He was content to live in and around the house for the next fifteen years.

Photo by Amy Larsen.