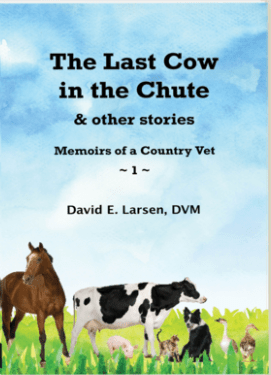

My ebook for The Last Cow in the Chute will be available for FREE this Saturday and Sunday.

https://www.amazon.com/Last-Cow-Chute-other-stories-ebook/dp/B093KKGW73/ref=sr_1_1?crid=10U1WVMFA2IQ5&keywords=the+last+cow+in+the+chute&qid=1625783719&sprefix=the+last+cow+in+the+chute%2Caps%2C236&sr=8-1

Free Book Promotion

Saturday, July 10, 2021, 12:00 AM PDT Sunday, July 11, 2021, 11:59 PM PDT

A Leap of Faith

D. E. Larsen, DVM

Preface: The summer following my sixth-grade year, Dana Watson and I thoroughly explored all the lands between Broadbent and Gaylord and over the hill to Yellow Creek. That covered a circular area of about 15 square miles. We climbed cliffs, traversed Neal Mountain, followed streams, and marveled at the engineering of beaver dams. We were vaguely aware of property lines but had no concept of trespass in those years.

***

I could hear Mom moving about in the kitchen when I laid in bed in the upstairs boy’s room. I nudged Dana awake.

“Dana, I have been thinking that we should go home to your place over Neal Mountain today,” I said as soon as he stirred.

“That would be a good idea,” Dana said. “I could show that large Beaver dam I was telling you about.”

We both bounded out of bed and dressed quickly. It was a cool summer morning with a dense covering of coastal fog. That meant that we had a few cool hours before the fog would burn off and expose the bright sun. But with the morning fog, even the hottest days would only be in the low eighties.

Mom had a plate of pancakes and bacon on the table when we tumbled down the stairs to the kitchen.

“When we go to Dana’s this morning, we are going to go over Neal Mountain,” I said to Mom, more to inform her than to ask permission.

“You two have been that way before, haven’t you?” Mom asked.

“It is a steep climb, but other than that, it is an easy route,” I said. “Once we cross over onto Mr. Neal’s place, it is all downhill.”

“What does Mr. Neal think about you traveling across his place?” Mom asked.

“We just go down his far fence line,” Dana said. “He wouldn’t say anything, and if he wanted to make a thing of it, we could just cross the fence. It just that there is a lot of brush on the other side of the fence.”

“Maybe I should call your mother,” Mom said. “Just to let her know where you guys are going to be.”

“They were going to Coos Bay this morning,” Dana said. “She probably won’t be home until after we get there.”

“Okay, but you be careful,” Mom said as we finished eating and headed out the door.

We headed across our upper field on a trot. Our plan was to reach the top of the shoulder on Neal Mountain before the fog burned off. The heat from the sun would make the climb up the steep slope difficult.

We crossed the line fence onto Herman’s and continued up the road to the old mill site. We gave the sawdust pile, left from the mill, a wide berth. Smoke rose from several holes around the parameter of the sawdust pile.

We knew these sawdust piles burned for years from spontaneous combustion. There were many horror stories of kids getting too close and falling into a burning hole. I doubted the truth of the stories, but not so much as to want to get too close.

We crossed the creek here and rested in the cool breeze coming up the stream. Now it was all uphill to the crest of the shoulder of the mountain.

We took a deep breath and started up the sloop. Dana led the way, almost crawling at times. We used branches to pull ourselves along on the really steep spots. Finally, we hit a well-worn trail, probably made by deer, but we liked to think it was an elk trail.

“Wow, this is so much better,” Dana said. “This is wide enough. It has to be an elk trail.”

The only place I had seen an elk was in the higher elevations of Eden Ridge and Bone Mountain.

“I don’t know, Dana,” I said. “I don’t think we have elk down here.”

“They could live on this mountain, and nobody would ever see one,” Dana said.

“I bet this is a cow trail,” I said. “We have cows that come to our place, and to Herman’s, from over the mountain. But it doesn’t matter. It makes the trip easier.”

Sure enough, we followed the trail to the crest of the shoulder, and there was a hole in the fence. We threaded our way through the fence and almost ran down the other side.

When we came to the fence at the bottom of the hill, we were careful in crossing it. These old ranchers would complain if we stretched the wires.

“That beaver dam is up the creek at the bottom of this hill,” Dana said as we continued on down the hill.

There was still a good flow in the creek for mid-June. We followed the stream through some pasture land for about a half mile before coming to the beaver dam.

This dam was about three feet tall and made with barked tree sections three inches in diameter and four feet long. There was a large pond behind this dam, and the water flowed over the top. This dam was solid as could be. We crossed the creek on the dam, jumping up and down in a few places to test its construction.

“My folks aren’t going to be home until later this afternoon,” Dana said. “Why don’t we go over and climb those cliffs by Gaylord?”

“Maybe we should stop by your house and let them know where we are going,” I said.

“My brothers don’t care,” Dana said. “And it would take us twice as long to get to the cliffs. Let’s just cut across these fields.”

And off we went, again at a trot. We were at the base of the cliffs in no time. These were exciting cliffs. This solid rock wall was pockmarked with shallow caves halfway up the cliffs. Some said it had probably been on the edge of an ancient ocean.

We went from one shallow cave to the next, almost in a stair-step fashion. There was a deeper cave in an indentation of the cliff wall. We climbed up to it and found that it went about ten feet into the rock wall before narrowing to an impassable passage. We found some bugs on the walls of this cave. They were nearly an inch long and were strange-looking. Sort of like a cross between a long sowbug and a grasshopper. When we would try to catch them, they would jump at us like a grasshopper. That was enough of that, and we went on to explore more of the cliff.

That is when we found it. We could see what looked like a nest of a hawk or eagle on the ledge above us. We needed to get onto that ledge.

The problem was, the ledge was sort of an overhang. We tried several approaches but could not get up to the ledge. Finally, Dana climbed onto my shoulders, and he could then pull himself up to the ledge. Then he laid on his stomach and extended his arms where I could just reach them. With Dana pulling and me digging for every toe hold, I finally made it up to the ledge also.

This ledge was was five feet wide and had a shallow cave on the cliffside. What we had thought was a nest may have been one at one time. But it was long abandoned at this time. We looked at every crevice, thinking we could maybe find an arrowhead or something.

After spending nearly a half-hour on the ledge, we thought it was time to get down. Suddenly, the overhang loomed largely.

“I don’t think we can get down without falling,” I said as I looked at the smaller ledge below us. The ledge we were on hung out a foot or two beyond the ledge below us.

Dana laid down and looked. “There is no way we can land on that ledge.”

“Now, what are we going to do?” I said.

“Nobody is going to miss us until dark,” Dana said. “And then they are going to be looking on Neal Mountain, not here.”

We sat and pondered our situation for a time. Then it was time to do something. Anything was better than nothing.

“Let’s start looking for another way down,” Dana said.

I went to the right side, I could see a route up to another ledge. Maybe there would be another way down from that ledge.

Dana went to the left side and disappeared as he crept along on a narrow ledge that ran along the cliff wall. I waited for his report before climbing up to the next ledge.

Suddenly, Dana called out from below. He was on the ground.

“Just follow that little ledge around the corner, and you can jump to the top of a fir tree,” Dana said. “Just grab the branches and slide down the outside of the tree. The last branch will put you almost to the ground.”

I started around the ledge with my back to the cliff wall. It seemed to get narrower the further I went. When I was across from the tree, I stood on my heels.

The top of the fir tree was just a little higher than my head, and it was a full thirty feet to the ground. Dana came back to coach my jump.

“Jump hard, and you will catch the tree about five feet below where you are standing,” Dana said.

“Jump hard,” I thought. “How the hell do you jump hard?”

I squatted down by sliding my butt down the wall to give my knees some flex. Then I exploded into the air with outstretched arms. When I slammed into the tree, I grabbed an armful of branches.

I stayed put for a moment, clutching the branches to my chest.

“Now, just relax and slide down the branches,” Dana said, reminding me that I was still twenty-some feet from the ground.

I relaxed my grip, and to my surprise, I slid down to the next set of branches. After that bit of a confidence builder, I slid all the way down, with the last large branch lowering me to the ground.

“See how easy that was?” Dana said.

I smiled and wiped my hands on my shirt. Pitch, I was covered with pitch. There was almost nothing on earth that I hated worse than pitch. That is, except for squash. I really hated squash.

“I have pitch all over me,” I said. “I hate pitch.”

“That’s alright,” Dana said. “Dad has some soap that will take it all off with no problem.”

We started off toward Dana’s house.

“I wonder how long it would have taken them to find us?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Dana said. “But I don’t think we should be telling anybody about this.”

Photo by D. E. Larsen, DVM