D. E. Larsen, DVM

“Hi Doc, I’m glad you could come this morning,” Harry said as he stepped out of the mobile home into the morning mist. “I have a couple of new calves with diarrhea. They are still up and around, but I don’t want to take a chance on losing them.”

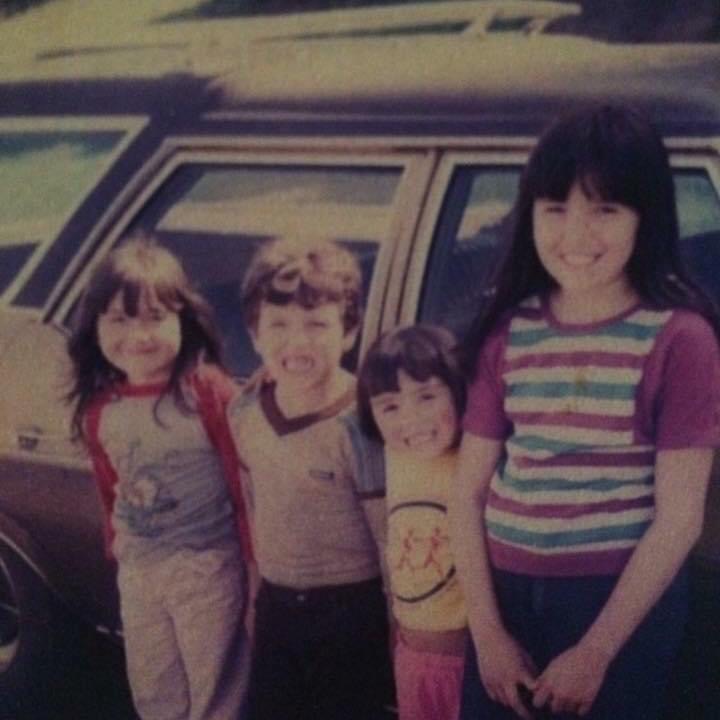

A couple of young girls followed Harry out of the house as he motioned me toward a small shed down the trail. The morning mist was getting heavier, almost a light rain, and there was still some fog that hung over the river.

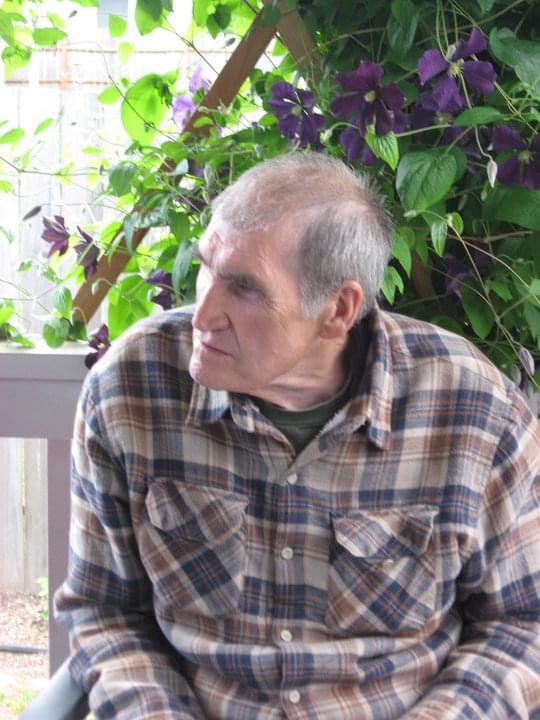

Harry was an older man than I, probably in his 50s. Tall with thick dark hair that had just a touch of gray. His features were rugged, telling of hard work in his life. His voice was different for Western Oregon, a strong Southern drawl was my first impression, but that didn’t really fit. Maybe from the Appalachian regions, I was guessing now.

“Did you get these calves from the sale?” I asked.

“No, I know a guy who got them from a dairy, out in the valley,” Harry said. “I know better than to buy those poor baby calves at the sale barn. They get exposed to every bug in the county. Some of them don’t last a week.”

I started looking the calves over. They were bouncing around and sucking on my pants leg or anything else they could get their mouth around. Temperatures were normal, and their navels were okay and looked like they had been treated with iodine. The shed was not much, but it was watertight and windproof.

The girls were joined by a boy now. They were hanging on the fence rails of the calf pen as I was trying to crawl back out. I don’t think Harry had stopped talking the whole time I was looking at the calves. I admit that I am not always a good listener when I am working, but he was talking about raising calves in North Carolina, Tennessee, or someplace back there.

“Harry, I think these calves are going to be fine with a little medication,” I said. “They are probably just a little upset with the move and the change from milk to milk replacer. I am going to give them a dose of BoSe, which is a Selenium and Vitamin E supplement that calves need here, some antibiotic tablets, and a couple of doses of oral fluids to use this evening and in the morning instead of their milk replacer. That will give their gut a chance to rest a bit.”

After treating the calves and giving Harry the additional medication, we started walking back to the truck. Harry proved to be much more of a talker than I was.

When we got to the truck, and I put things away, got out of my boots and coveralls, Harry was still standing there in the rain with no hat, talking away.

“We come here to take care of these kids,” Harry says. “Their father died last year, and then their mother, our daughter, was killed in a car accident this summer.”

I didn’t know what to say, I wished then that I had been listening to him a little better when he was talking earlier. What kind of a man, a couple, does it take to pull up roots to take care of their grandkids. And what an undertaking, to raise young kids at his age.

Harry didn’t let my lack of response slow him much. He continued to talk. The rain was dripping off his eyebrows and his nose, he didn’t notice. We stood there in the rain, my schedule faded into the background, and Harry talked, I listened. My respect for the man grew by the minute, which probably came close to an hour.

Harry had a lot of knowledge of livestock, but it was from a background that was not familiar to me. Most of his understanding seemed close to correct, but just seemed based on a different set of standards than I was used to, sort of like something you would read in Fox Fire.

The kids would come and go, mostly because they tired of standing in the rain. Harry would put a hand on their head or shoulders as they stood close, but it did not slow his conversation. We were both soaked when I finally got back into the truck.

I would see Harry from time to time, for little things mostly, but it was a couple of years before he called for some cow work. He had moved to a small farm on Hamilton Creek at the time. He had a heifer that needed to be dehorned.

Harry and his crew were racing to the barn as I came to the end of the long driveway. The kids were older now, and they were actually helping instead of just being in the way. I know how that made them feel because I was always at the barn from the time I was three. I always felt almost grown-up when I could actually do something helpful.

“I got this heifer for an excellent price,” Harry said. “She is pretty handy with those horns, though. I don’t know why people don’t get them off when they are babies? It is so much easier then.”

“This won’t be a problem for her,” I said. “We are early enough that flies won’t be a problem and late enough to be done with most of the rain.”

“The kids are worried that it is going to be painful,” Harry said.

“I will show them how to give an injection of Lidocaine,” I said. “We will numb these horns up, and she won’t feel a thing.”

Deshawnda and Nathan had the heifer in her stanchion and a rope halter on the heifer already. I think they didn’t want me to use my nose tongs. I pulled the head to the right and tied the lead rope to hold it there.

I drew up 10 ccs of Lidocaine in a syringe and pointed to the four points I was going to inject to completely deaden the horn. Actually, when I did a group of heifers, I would only block the main nerve at the base of the horn at the 6:00 o’clock position. The injections were completed effortlessly with the head well secured.

“This is going to smell a little bit, sort of like burnt bone,” I said as I place an OB wire saw around the base of the horn.

I leaned back, putting a lot of my weight on the wire. I wanted to go quick, but also I wanted the wire to get hot enough that there would be little or no blood.

With a number of long strokes of the wire saw, the horn popped off. It was a clean-cut, and the vessels were sealed from the heat of the wire, and not a drop of blood for the audience. The frontal sinus was open, leaving a gaping hole, which was typical for this age of heifer.

Harry picked up the horn from the ground and glanced at it. His face fell as he dropped the horn back to the ground.

“Oh no,” Harry said as he turned and stepped into the barn.

I repeated the process on the other horn and pulled all the vessels so there would be no bleeding. I covered the openings to the frontal sinus with a patch of filter paper. It would only last a couple of days and probably served no real purpose, but I thought it might make Harry feel better.

I was just finishing up when Harry came back from the barn.

“How bad is it, Doc?” Harry asked. “She is such a nice heifer, it makes me sick.”

“How bad is what, Harry?” I asked.

“The Hollow Horn,” Harry said. “I saw the horn, how bad do you think it is going to be for her?”

“Harry, in a heifer of this age, a hollow horn is normal anatomy,” I said. “The frontal sinus extends out into the horn. The old disease called Hollow Horn was one way of explaining what was wrong with a cow when they couldn’t know what was really wrong. Those names and disease explanations were used before we knew much about parasites, viruses, and bacterial diseases.”

“You think she is going to be okay?” Harry asked.

“She is going to be fine,” I said. “This dehorning is not going to slow her down one bit. Those holes into her frontal sinus will heal with no problem.”

“Okay, Doc, I trust you,” Harry said. “I have heard of Hollow Horn my entire life, but I had never seen it before.”

We turned the heifer out into the field, and she joined the others and started grazing as if nothing had ever happened.

Photo Credits: Dye family photos