First published July 12, 2021

D. E. Larsen, DVM

By the summer of nineteen sixty-seven, I had been elevated to Quality Control NCO in our maintenance shop for the 177th USASA Operations Company located at Camp Humphreys, South Korea.

The year I was there is often called the second Korean War. We were besieged by many infiltrators from North Korea that year. Firefights on the DMZ were regular events. In that year, we lost over six hundred UN soldiers. Over one hundred of those were Americans.

The 177th was the hub of the low-frequency radio intercept and direction finding operations in the country. We had a lot of equipment to maintain, both installed in our operations and mobile vans.

This position removed me from the rotating trick maintenance position and gave me a day job. That was a blessing, but the position also gave me a couple of headaches, namely, in Dumb and Dumber. The two trick workers could also be called Mutt and Jeff. They seemed to do everything together, and their work often had to be redone by someone more competent.

Promotions were given out almost automatically in Korea. Nearly everyone in the shop was promoted to Specialist Five when they had two years in the Army. I wondered why these were still Spec Fours, and they were close to rotating to their next duty station.

“Dumber, I have a job for you,” I said as I assigned Dumber to fix a mobile jamming transmitter located down at the motor pool.

“Great,” Dumber said, “I will take Dumb with me. We can go to lunch when we are done. That will get us out of the shop for a few hours.”

I had a strange foreboding as the two left the operations building, carrying an armload of equipment each. They still managed to laugh and butt shoulders as they went through the exit door.

Starting at ten-thirty in the morning, most of the guys in the shop would have had the job done well before lunch. But actually, having the pair out of the shop for a few hours was a good thing, so I let them work at their own pace.

When Dumb and Dumber returned to the shop, it was nearly two o’clock.

“I thought you two would be back right after lunch,” I said.

“We got the transmitter fixed and checked out its operation,” Dumb said. “Then, after lunch, we had to go back to the motor pool and get all our equipment. We got back as soon as we could.”

Their explanation was marginal, but there was no sense in questioning their time frame. They settled into the afternoon work schedule, and everything was going along fine.

That is, going fine until Chief Warrant Officer Neal, the officer in charge of the shop, stormed across the hall from his office.

“I have the old man on the phone, and he is really pissed,” Mr. Neal said. “It seems we have been jamming a local radio station for the last several hours. Do you know anything about this?”

I looked at Dumb and Dumber; no words were needed. They immediately fessed up.

“We fixed that transmitter and rolled it up on this Korean radio station, just to check it out,” Dumber said. “I guess we must have forgotten to turn it off when we went to lunch.”

Mr. Neal fumed. Steam was coming from his ears.

“You get your ass down there and turn the thing off,” he yelled to Dumber.

Then he turned to me. “You should know better than to send that pair to do anything without direct supervision,” he said. “That means they don’t do anything out of this shop.”

So Dumb and Dumber were sent to visit with the commanding officer. They were given an article fifteen for lack of detail in the performance of their duties. Article fifteen, a company-level punishment, just about confirmed that they wouldn’t be promoted before leaving Korea.

***

It was a sweltering hot August afternoon when the Swing trick took over for the trick on days. Everyone wanted to be in the operations building. It was about the only place with air conditioning in this section of Korea.

I was just leaving the shop when I heard the trick chief handing out assignments for his crew. They had to run the emergency generators today. I cringed when I heard him give the job to Dumb and Dumber.

“You know the situation,” I said to the trick chief. “Those two are not to be doing anything outside of the shop without direct supervision.”

“The generators are inside the compound,” the trick chief said. “They have done this every time we have the assignment.”

We had two massive diesel generators for emergency power that were manually started, stabilized. Then they were switched over to run the operations building. The Comm Center had its own generator that would automatically switch on in the event of a power failure.

We ran the operations building on emergency power for a half-hour every month. Just to make sure the generators were operational and that the maintenance crew was familiar with the operation and switch over protocol.

That protocol required the generator to be started and stabilized before switching the site over to emergency power. Although the switch would only cause a blink in power, we would always have the equipment turned off before switching over to the generator.

I left with the rest of the day crew, and we went down the hill to mess hall for dinner. We were through the chow line and had just started to eat when one of the swing trick guys came running into the mess hall.

“You guys are needed back at the shop, stat,” the guy said.

“Can we finish dinner?” I asked. The mess hall had Korean servers and cooks, and the was no shop talk allowed at any time.

“No, we need all hands on deck immediately,” the runner said.

Climbing the hill back to the operations building in the afternoon heat was not the most pleasant exercise method. But the gem at the end was an air-conditioned building, so that made the task bearable.

When we checked in through the security gate, the guard said, “You guys had better hurry.”

We walked into a completely dark operations building. The smell of burnt power supplies was overwhelming.

“What happened?” I asked the trick chief.

Mr. Neal almost ran over me as he rushed through the door of the operations building.

“What happened?” Mr. Neal asked.

“Every light bulb in the building is burned out,” the trick chief said. “Even the light bulbs in the comm center. Apparently, their lights are not hooked into their emergency power supply. And almost every piece of equipment has a blown power supply.”

“That doesn’t answer the question,” Mr. Neal said. “I want to know what happened.”

“Apparently, when Dumb and Dumber switched the site to emergency power, they hadn’t stabilized the generator. It dieseled on them, and it must have put three or four hundred volts of power into the building. They hadn’t told anybody they were making the switch, so all the equipment was still turned on and operating. Most of the power supplies are toast, as you can smell.”

“I want those two out of operations,” Mr. Neal said to the trick chief. “They can pull weeds for the old man until they rotate out of here. And you knew they were not to do anything out of the shop. You are going to have some explaining to do.”

“They only have a couple of weeks before they rotate out of here,” the trick chief said.

“God, I hope they aren’t getting sent to Vietnam,” Mr. Neal said. “They will get a lot of guys killed down there if they pull a stunt like this. It is bad enough here. How long until we can get things back online, Larsen?”

“If we get some lightbulbs working, we can get some stations working in a couple of hours,” I said. “We are going to be limited on the supply end.”

“You let the operations officer select the stations he wants up first,” Mr. Neal said. “I will start working on the supply issues. We are probably going to have to bend a few of those Army rules.”

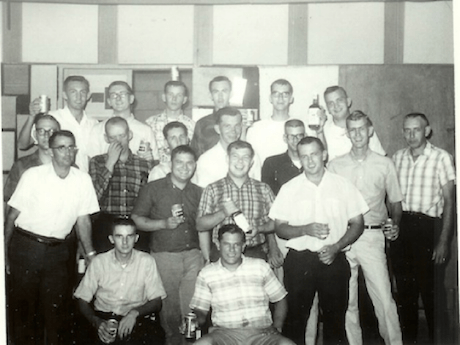

And so it began, nearly forty-eight hours of work before the operations were fully functional again. Then a few hours of sleep and a big party to celebrate the fix.

Dumb and Dumber were just gone. I have no idea what became of them, but they were shipped out to Seoul, I would guess.

Photo from Victor Hugo, seated, front left.