D. E. Larsen, DVM

A little history on the Calf Scramble at the Coos County Fair, first, then Queenie’s story.

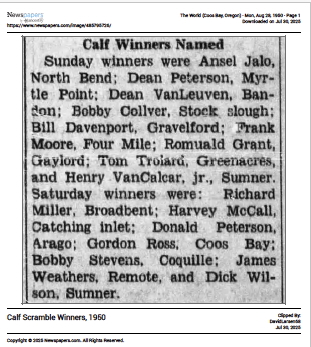

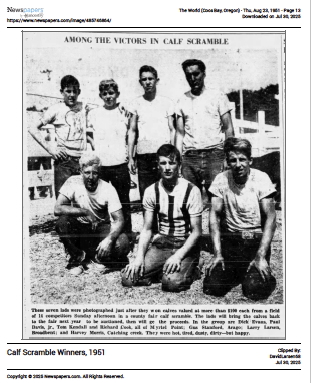

The Coos County Fair and Rodeo in Myrtle Point, Oregon, started in 1912. The Calf Scramble was added to the Rodeo program in 1949. In the initial years, steer calves were used in the calf scramble. I have been unable to determine the year when the switch to heifer calves was made.

But heifers were used in 1959.

As near as I can determine, the

last Calf Scramble was conducted

In 1987.

David Larsen, 1959

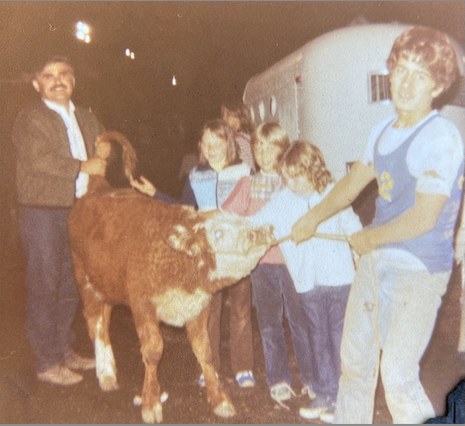

I had several family members who

won scramble calves.

Bill Davenport, cousin, 1950

Larry Larsen, brother, 1951

Aaron Larsen, Nephew 1976

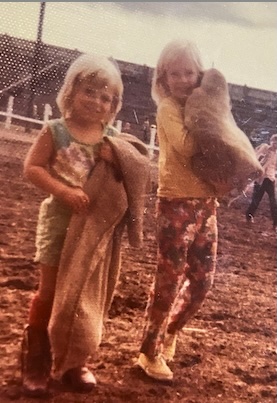

Debra & Laura Larsen,

Chicken Scramble 1974

Chickens in the gurney sacks.

Now, on to Queenie’s story.

By the beginning of summer in 1960, Queenie was settled into the routine of following the dairy cows to the barn every morning and late afternoon. The trails were worn deep in the pasture as the cows joined the single-file line to the barn with only the slightest encouragement.

Queenie was a well-conditioned Hereford heifer, after a winter of corn silage and grain. With a bit of sleuthing, unknown to my father, I increased her grain ration as the summer progressed.

The summer was filled with preparing Queenie for the show ring at the County Fair in the middle of August. That meant hours of training her to lead and to stand correctly. Trips to the bathing rack. And curling her hair coat.

After my years in 4-H, I was well-versed in showmanship. But my experience was with dairy animals. The beef folks used different methods for positioning an animal’s feet by using a show stick.

After several attempts with the show stick, Queenie learned the kinder dairy methods of a nudge here or there. But when the fair came, Queenie was ready.

The fair was busy as always. The scramble calves were weighed and assigned to a special set of stalls, separate from the rest of the cattle, located right on the main entrance path.

Queenie weighed in at just under eleven hundred pounds. Second place, by less than ten pounds, to another calf raised with a dairy herd over on Coos River. I should have increased her grain ration earlier. Things were geared toward an auction for the scramble calves, but this year, that was not on the schedule. These calves were ours to keep.

When it was our turn in the show ring, Queenie placed second behind the Coos River calf, both a notch or two ahead of the rest of the group. Both myself and the Coos River kid were scolded for showing these calves like we would show a dairy animal. We had to stand at the head of the group and listen to how we should use a show stick, not just carry it.

All that meant nothing. We both got blue ribbons, and I had fulfilled my obligations to the fair board. Queenie was now mine. The trip back to the farm was an enjoyable one, especially for Queenie. She kicked up her heels when she was unloaded and turned back into the pasture with cows she knew.

She was a little disappointed when her grain ration was reduced.

“You need to cut back on her feed,” Dad instructed. “She doesn’t need to carry that extra weight. She will be coming into heat pretty soon, and we need to get her into shape for calving.”

I knew Dad was right, but Queenie did a double-take when I scooped a couple of handfuls of grain into the manger in front of her, rather than the two large coffee cans full of grain that she had been getting.

It was only a couple of weeks later when Dad met me at the barn door when I was coming to help with the evening milking.

“Queenie is heat today,” Dad said. “You need to go call to make sure we can get her bred tomorrow with an AI bull.”

Just a bit of excitement, but nothing major.

“Do you want a fancy bull?” Dr. Haug asked when I called.

“She is a scramble calf,” I said. “They said she was registered, but I don’t have any papers. Just a good Hereford bull will do.”

“Okay, I pick out a bull with a record for easy calving,” Dr. Haug said. “Can you get her in a stanchion?”

“Sure, she thinks she’s a dairy cow,” I said. “She has been coming to the barn twice a day for most of the year.”

“Great, just leave her in the barn and I will take care of her tomorrow,” Dr. Haug said.

That was simple. Queenie was bred and pregnant. She slipped into her routine with the herd of cows. School started, and football, along with other activities, became a part of an active teenager’s life.

It was almost a surprise when Mom came into the house one morning, all excited.

“Queenie had her calf last night,” Mom exclaimed. “It looks good from the front porch. Maybe you should run out and get a look at it before you leave this morning.”

I hurried through breakfast and pulled on a pair of boots. Queenie was in the far field, but Mom knew I was in shape enough to run out there and back and still have time to make it to school.

When I got to Queenie, she was just as gentle as she was at the fair. Her calf, already up and running about with a dry umbilical cord hanging from her navel, was not about to be caught. But I could tell it was a heifer calf.

“What was it?” Mom asked the minute I came through the door.

“It’s a heifer and everything looks good,” I said. “Queenie has passed her afterbirth, and the calf’s navel is dry. She must have been born last night.”

“That’s great,” Mom said. “That’s the way it is supposed to happen. Now you have two females in your herd.”

The following day, when I arrived from school, I looked toward the far field. I could see Queenie, but the calf was not to be seen. A little odd, I thought.

“I don’t see Queenie’s calf this afternoon,” I said when I hurried into the house to change clothes.

“It’s probably lying down somewhere,” Mom said. “That would be hard to see from here.”

“I will run out there before starting my chores,” I said. “Just to make sure it’s okay.”

I knew this field like the back of my hand. Catching Creek ran along one corner of the field, and the road ran along one side before turning left and running beside the creek to the upper reaches of the little valley.

The grass was not tall, and I made a quick circle of the field. Then I walked along the creek, through the brush, and watched for any sign of tracks. There was nothing. The calf was just gone. I stopped and scratched Queenie on her back as I headed back toward the barn. She didn’t seem to show any concern.

I repeated the process the following afternoon. There was no sign of the calf. I spent enough time to cover every inch of the field and the creek bank. I even went downstream looking for any sign of the calf, hoping that she didn’t fall into the creek.

“The calf is just gone,” I said at the dinner table that night.

“You don’t think someone stole that calf out of the pasture, do you, Frank?” Mom asked.

“I think they would have to be pretty fast to be able to catch it,” Dad said. “I think Queenie must have tucked away somewhere.”

The following evening marked three days since the calf had been seen. I searched along all the fence rows and into the adjoining fields. I stayed with Queenie until dark. She showed no signs of distress or concern.

I was sick. Mom warmed my dinner, and I sat at the dinner table alone.

“I guess she is just gone,” I finally said as I started upstairs to bed.

The following morning, I stood and watched Queenie from the porch before heading off to school. She was still by herself in the field.

I was miserable all day at school. I ran through my mind everywhere I had looked. There was one spot, a grove of large maple trees, where the creek and road parted ways. I had looked there, but I had not scoured the spot. Mainly, because it was just bare ground under those trees. But I resolved that tonight I would search that area. That provided me some comfort for the rest of the school day.

When the final bell rang, I bolted for the door. I was the first one on the bus and could hardly contain my excitement. I was convinced that tonight, I would find that little heifer calf.

My resolve to find the calf tonight was stronger than ever as I got off the bus and ran to the house. I was running the layout of the maple grove through my mind, trying to visualize just where that calf was hiding.

I reached the porch, and just before entering the house, I turned to look for Queenie in the far field. There she was, grazing on the lush pasture. And, running circles around her, there was her calf.

“The calf is back in the pasture,” I said to Mom when I came through the door.

She stepped out on the porch to look.

“I wonder where she has been all this time,” Mom said.

Before going to the barn, I ran out to the pasture to check the calf. She was fine, didn’t look like she had missed a meal. Her umbilical cord was gone. She came up and sniffed my pants leg as I scratched Queenie on her back.

“The calf is back in the pasture,” I said to Dad when I entered the barn.

“You’d better name her before she disappears again,” Dad said. “Have you thought of a name yet?”

“I think, Princess,” I said. “After all, her mother is a queen.”

“That fits,” Dad said. “By the way, I stopped by the cheese factory this afternoon and spoke with Art. He said you can start to work there this weekend. Check into the office at eight on Saturday morning to do their paperwork.

Life got busy for me at that point. The cheese factory was the best job in town, outside of working in the woods. Dad had worked as a logger for many years. He was anxious for me to get a job that was not in the woods. At the cheese factory, I could work after school and on weekends. I would have enough money for a car and the first year of college by the time I was out of high school. Then, working summers, I could pretty much work a summer and pay for a year of school.

Queenie and Princess stayed with the cow herd. Only Dad quit bringing her into the barn. When Queenie was ready, we bred her to the same AI bull that had given us Princess.

In the spring, I graduated from high school, and Queenie had another heifer calf.

There was no drama this time. We woke up one morning, and Queenie was out in the pasture with Princess and another calf. I ran out to check it, to make sure it was a heifer.

AS fall approached, I began thinking about going away to school. Don, a coworker at the cheese factory, asked me what I was going to do with my cow herd.

“You know, if you leave them there for you Dad to take care of and do all the work, he will start thinking they are his,” Don said during one break.

“Yes, I know,” I said. “He has to take the trouble of cutting them out of the herd at every milking now. That is sort of pain for him.”

“My herd is doing well and growing all the time,” Don said. “I could use a few good cows. If you are interested, I would like to buy them from you. That would give you a good cushion for school.”

I gave his words some thought. Queenie’s life would be good at Don’s place. The money would make my coming year comfortable.

Don and I reached a price and shook hands.

“I can come Saturday evening, probably after your milking time would be best,” Don said.

When I broke the news to Dad, he was not happy. Not about the sale, he had been thinking the same thing. But he thought the price was too low.

“This is a super group of young females,” Dad said. “You need to ask for more money.”

“We shook hands, Dad,” I said.

Dad shook his head. He had taught me well. And a handshake was stronger than any document a lawyer could write.

It was a little bit of a sad time when we loaded the Queenie, Princess, and Duchess into Don’s trailer. Mom put her hand on my shoulder, and there was a single tear on her cheek.

“Beef cows are happier on an open range,” Mom said. “They just get too fat when they are raised with dairy cows.”

Photo Credit: Mohan Nannapaneni on Pexels.

Bittersweet ending to a royal lot of Herefords.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Dr. Larsen, for the heartwarming story!

Joanna

LikeLike

Good writing, Doc! I enjoy these stories of the way life was back then.

LikeLike

I would have a hard time parting with those cows. What a wonderful story and beautifully written. You had me worried about Princess.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This story ended up great. I knew the Rood boys from Coos River! Was a counselor at 4-H Camp with Neil! Really like all the pictures!

LikeLike

The Coos River kid was a Rood. I couldn’t remember his name but I’m pretty sure it wasn’t Neil.

LikeLike

So that was the end of you being a cow farmer. You surely had an advantage at vet school and later knowing both sides of the trade.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very true. Veterinary Medicine in this country has run into a problem with many farm kids being beat out for admission by the urban girls. They are finally coming to the realization that all the cow doctors are my age. There are vast areas, covering multiple counties without a cow doctor. This is especially true in the midwestern states. Some schools are now reserving spots for farm kids.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And not one day too early – rather a decade too late

LikeLiked by 1 person