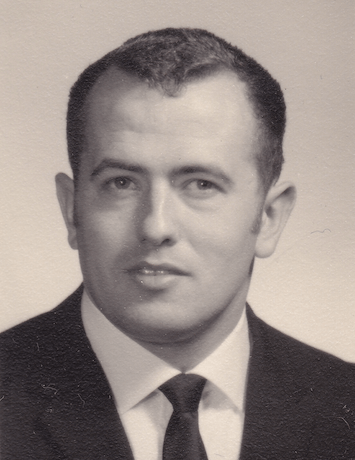

D. E. Larsen, DVM

Vertebrate Embryology class in the Zoology Department of the School of Science at Oregon State University was a required course for virtually all preprofessional students in 1969. That means that anyone hoping to get into medical school, dental school, or veterinary school was required to take this class. A good grade, preferably an A, was an unspoken requirement.

In the years before 1969, the series, which included two-quarters of Vertebrate Anatomy, was required. This was the first year that the requirement was reduced to just the embryology class.

These classes were taught by Dr. Hilliman. Dr. Hilliman was feared by most students in the class. He virtually held their futures in his hand and could scratch their dreams with a stroke of a pen. Rumor had it that he had just failed one of his Ph.D. candidates who had been studying under him for five years.

The lectures were held in a large auditorium in the Zoology building. I don’t know how many people were in the class, but the arena was packed. I would suspect there were nearly 600 students in the lectures. Then the class was broken into laboratory groups. Graduate students would conduct the weekly lab classes, and my lab class had about thirty students.

Historically, one of the main features of the fall term was a massive spelling test. This test included anatomy names and phrases extracted from all three classes in the vertebrate anatomy and embryology series.

This was the setting when Dr. Hilliman addressed the packed auditorium about the upcoming spelling test.

“This test will be from the list of words that will be handed out in your lab class this week,” Dr. Hilliman said. “This word list is derived from words in this class and the two anatomy classes. This test is heavily weighted in my grade book.”

I was thunderstruck. How could he justify testing over classes that are no longer required? I waited for the uproar from the class.

Not a word was said. The entire auditorium was silent, not even a moan. There was nobody brave enough to question this man.

I was mere weeks from the days when I gave presentations to visiting generals and NSA bigwigs in the general staff meetings at Wobeck. Those men actually held men’s lives in their hands. Those men had actual power. This professor was nothing compared to those men.

I took a deep breath and stood up. An audible gasp rose from the depths of the auditorium. Dr. Hilliman actually looked shocked as he looked at me. Someone was actually standing to address him. But he did not say a word to acknowledge my standing in the middle of this huddled mass of students.

Finally, I spoke in a firm, loud voice so all could hear.

“Dr. Hilliman, I am David Larsen,” I said. “I know this is a historical test, but this year, the requirement for the two anatomy classes has been dropped from the preprofessional requirements. The majority of students in this class today will not be required to take those classes. I think it is grossly unfair to be tested over material that we will not be required to take.”

When I was finished, I continued to stand. Dr. Hilliman seemed to glare at me, but he was too distant for me to appreciate that glare.

“Sit down,” Bob, a premed student sitting beside me, said as he tugged at my shirt. “Your dead, you know.”

Full minutes passed as Dr. Hilliman contemplated how to address this lone student who dared to stand and question the very conduct of his class. Did this fool not know his stature, the power he wielded over this group of wannabes. There was a hushed silence in the auditorium as everyone waited for the explosion.

“I have given this test every fall for over twenty years,” Dr. Hilliman finally said. “In that time, not one student has stood up and complained about this test. How dare you question my intentions.”

“I know the history of this test,” I said. “But this is the first year in the change in requirements. I say again, most of this class will not be required to take the two anatomy classes included in this test. And, I do not think that is fair.”

“The test will be conducted in your lab classes in three weeks,” Dr. Hilliman said. “Its format will be unchanged.”

That sounded like the discussion was over. I knew enough to not push too hard and try to get in the last word. I sat down.

“Why did you give him your name?” Bob said. “He is the most vindictive man on campus. You’re dead for sure.”

“What is he going to do? Send me to Vietnam,” I said.

Bob looked with a question in his eyes.

“That is the standard Army threat,” I said. “Do this the way I say, or I will send you to Vietnam.”

***

The following week, Dr. Hilliman appear in my lab class. He came through the door and stood in the corner as the graduate student was finishing some instruction. When she was finished, he came over and pulled up a chair to the table that I shared with Bob. He laid his grade book on the table.

“How are you doing today?” Dr. Hilliman asked.

“I’m doing fine,” I said.

“I have been looking at my grade book,” Dr. Hilliman said. “You are doing quite well. Not the top of the class, but close.”

“I enjoy your class,” I said. “That makes it easy.”

“You are a little older than most of my students. Can you tell me a little about yourself?”

“There’s not much to tell. I grew up in Myrtle Point. I didn’t do well in my first couple of years of college. So I spent nearly 4 years in the Army. That gave me some maturity, some direction in my life, and a sense of responsibility to my fellow man.”

“The other day, when I said nobody had ever questioned me in class, I meant it. I all my years of teaching, nobody has stood up in my class like you did.”

“Everybody is afraid of you,” I said. “You intimidate them.”

“You’re a good student. A little anatomy test should not be an issue for you.”

“But it might be for some of your students,” I said. “Like I said in class, it’s not fair. The test is not fair, and your intimidation is not fair.”

Dr. Hilliman sort of recoiled at that statement.

“What makes you so different?” he asked.

“My experience base is a bit different than a lot of your students,” I said. “Fear and intimidation is no way to lead men, or women, for that matter.”

***

The test turned out to be no big thing. It was a snap, in fact. It was one of the few things I studied for that fall, and getting an A was the expected result.

Following the test, the lab instructor handed me a note. It was from Dr. Hilliman, with an invite to visit him in his office.

“I have never seen Dr. Hilliman take a personnel interest in an undergraduate student,” the lab instructor said. “Your standing alone, in the middle of the auditorium the other day, must have made quite an impression on him. Good luck with the meeting.”

In my remaining two years at Oregon State, Dr. Hilliman remained a good friend and advisor. Unlike his reputation, I found him a cheerleader for my progress and an excellent reference for my applications for veterinary school.

Photo by D. E. Larsen, DVM

Dear Sir…You stood up for what you believed in. Good for you.

LikeLiked by 4 people

I enjoyed reading this story! I am proud of you for taking that initiative on behalf of your fellow students. That time in the Army was well spent.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That time in the Army was a very positive experience for me. I know that was not the case with a lot of veterans, but you sort of get out of something, based on what you put into it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You have then proven that it is worth to stand up to power, if one does so respectfully (which you did), and with reason (which you also did). I found that true for a lot of ppl in the teaching profession, sadly not in later life.

LikeLiked by 3 people